The 2026 ski season across the Western United States has been nothing short of a hot mess, and at this point, there’s no way to spin it — this winter has been, let’s say, less than ideal. And the numbers back this up, especially when considering the broader Western Ski Season trends.

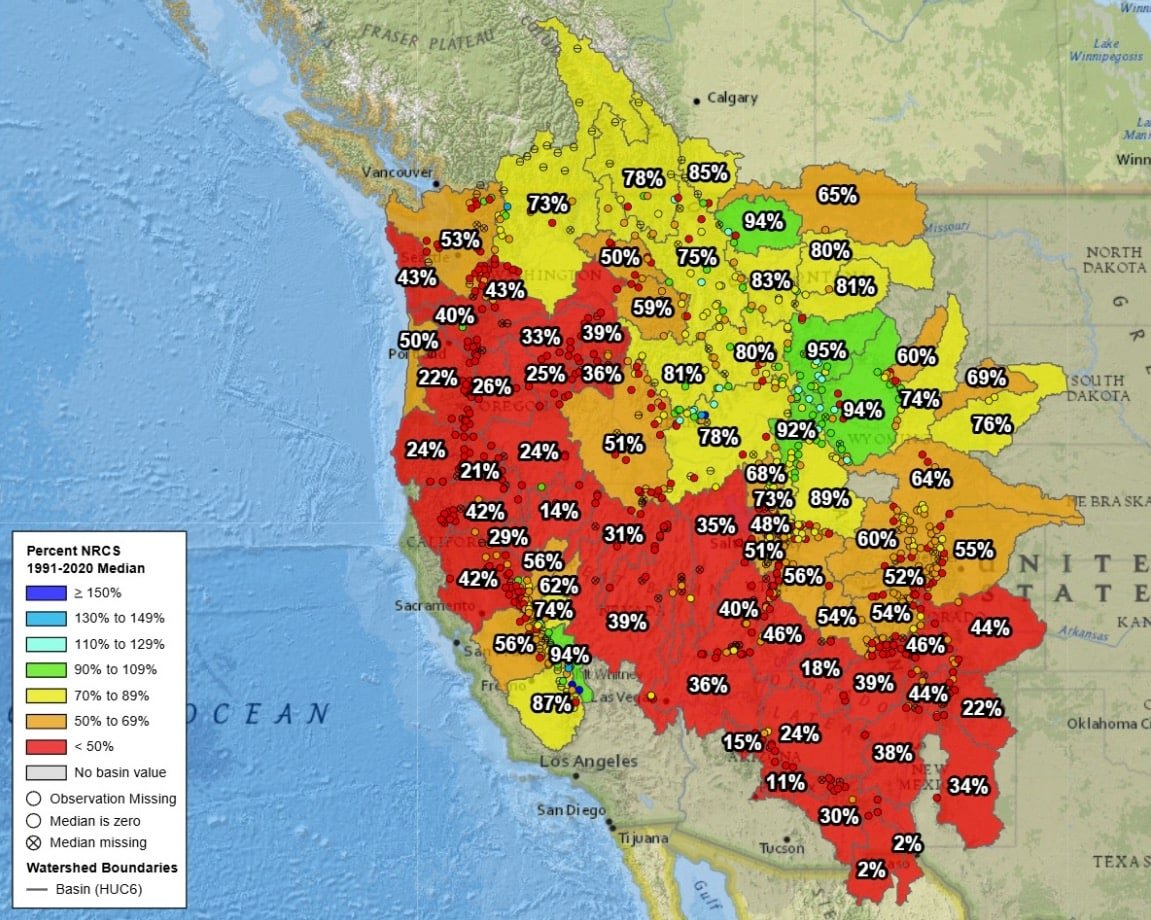

USDA NRCS data comparing current snow water equivalent to the 1991–2020 median shows massive swaths of the West sitting well below average, with many river basins under 50% of normal and large areas in California, Nevada, Arizona, New Mexico, Utah, and parts of the central Rockies dipping into the 20–30% range. The map is dominated by red. Even traditionally reliable snow zones have struggled to stay near average, while much of the Southwest looks more like late April than mid-winter. Federal snow monitoring has shown that snow-covered area across the West dropped to roughly 34% of the long-term average at one point this season — the lowest in the satellite record — underscoring just how widespread and abnormal the lack of snow has been throughout the Western Ski Season.

On the ground, the impacts have been painfully obvious. Early season warmth meant rain instead of snow at many elevations, and by Thanksgiving, only about 11% of the terrain across Western resorts was open. Resorts leaned hard on snowmaking just to spin lifts, but you can’t manufacture a full mountain. Vail Resorts CEO Rob Katz told investors that the West saw “one of the worst early season snowfalls in over 30 years,” a statement that aligns with what skiers have been seeing with their own eyes and perfectly illustrates how challenging the Western Ski Season has been.

The New York Times summed it up in stark terms: “In the Western United States, the 2026 ski season is shaping up to be one of the worst in decades.” Utah’s assistant state climatologist even noted that Florida’s Panhandle had seen more snow than Salt Lake City at one point this winter — a sentence that feels almost impossible to write about a state synonymous with powder. Colorado resorts have reportedly experienced around a 20% drop in skier visits compared to last season, a significant hit for an industry that drives billions in economic activity. In California, Mt. Shasta Ski Park has been forced to temporarily close after rain and warmth wiped out what little base had formed, leaving slopes muddy and unskiable. This kind of disruption is something unique to the difficulties facing the Western Ski Season during 2026.

While occasional storms have brought brief refreshes, they’ve been too little and too inconsistent to dig the West out of its deficit. The bigger concern goes beyond lift lines and powder days. Low snowpack means reduced spring runoff, raising concerns about water supplies for cities, agriculture, and hydropower across the region. It also increases the likelihood of drought stress and sets the stage for a potentially intense wildfire season if the dryness persists into summer. For mountain towns that depend on winter tourism, the ripple effects are real — fewer visitors mean fewer hotel bookings, restaurant tabs, and seasonal jobs. Additionally, the Western Ski Season’s struggles impact both local economies and broader environmental health across the western states.

There’s always hope for a miracle March or a late-season turnaround, and Western skiers know better than anyone that winter can flip the script fast. But as it stands now, the 2026 season is shaping up as one of the most disappointing and snow-starved in decades. For an industry built on deep days, storm cycles, and powder panic, this year has been defined by brown hillsides, thin coverage, and a whole lot of checking the forecast only to come up empty. Unless something dramatic changes soon, this winter will be remembered not for legendary lines — but for how little there was to ride throughout the Western Ski Season.